Constitution Day 2011

Martyr Lincoln's Constitution and a New Birth of Freedom

By William Woodward, Ph.D.

Professor of History

Seattle Pacific University

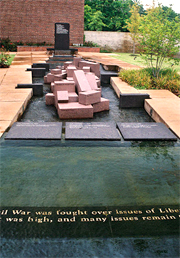

In Corinth, Mississippi, at a National Park Service Civil War interpretive center, a fascinating water sculpture tries to represent America’s story from its hallowed founding ideals through its tragic Civil War. Artfully engineered to picture episodes of both crisis and resolution between the Constitution’s approval in the 1780s and the nation’s post-war reunification in the 1860s, it’s a remarkable blending of kinetic art and hydraulic engineering, particular historical episodes and universal philosophical questions.

In Corinth, Mississippi, at a National Park Service Civil War interpretive center, a fascinating water sculpture tries to represent America’s story from its hallowed founding ideals through its tragic Civil War. Artfully engineered to picture episodes of both crisis and resolution between the Constitution’s approval in the 1780s and the nation’s post-war reunification in the 1860s, it’s a remarkable blending of kinetic art and hydraulic engineering, particular historical episodes and universal philosophical questions.

It thereby aptly highlights the enduring significance of the U.S. Constitution and its most deadly crisis, the American Civil War. And it offers a useful focal point for reflection on Constitution Day 2011.

Although national memory in September 2011 centers on the 10-year anniversary of a still-vivid national horror, this year is also the sesquicentennial of that great Civil War – a more catastrophic though more distant tragedy and test. So it seems fitting to return for a fourth time to the powerful impact of the war on the American Constitution.

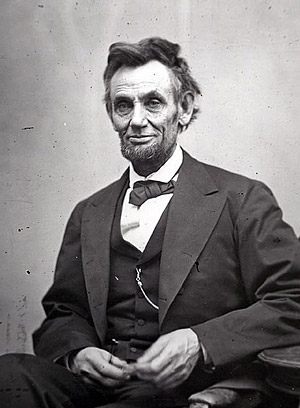

I have recounted this story through a distinctive lens: the remarkable lawyer, orator, and moral leader whose fate it was to serve as President in the dark hour of national disunion and bloodshed. I have analyzed in turn Lincoln’s arguments against slavery, against secession, and in defense of his extraordinary exercise of presidential power.

A Constitutional Vision

Abraham Lincoln in life, so respectful of the great charter documents, the Declaration of Independence of 1776 and Constitution of 1787, taught us why slavery and rebellion could be constitutionally opposed. In death, as well, the martyred president spoke, offering a pathway to reunion different from an instinctual vengeance. Rather he famously called for “malice toward none, with charity for all.” But he also led a process toward institutionalizing in the Constitution itself what had been painfully won in battle. His assassination cut short a role in steering amendments through to adoption. But the legacy of his morally and historically grounded constitutional vision inspired the process.

Perhaps Lincoln’s greatest statement of that vision came in the midst of the war, in the famous Address at Gettysburg at the dedication of the National Cemetery there. He first evoked the founding values of liberty and equality. The present war, he then said, is testing “whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” And at the end of his incisively short speech, he returned to the future, calling America, “under God,” to “a new birth of freedom” to ensure that “government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

How then to embed in America’s principles and practice not just the ideals of liberty and equality for all, but the practical guarantees and prohibitions that could secure those ideals? How, in short, could the Constitution be amended to enshrine that “new birth” that the Civil War had been fought to achieve: a rebellion crushed, a union restored, and a people once held in bondage made free?

In answer, this year’s Constitution Day reflections focus on the three so-called Reconstruction amendments – the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth – the lasting Constitutional legacy of the martyred president.

The Thirteenth Amendment

Abraham Lincoln released the final wartime Proclamation freeing slaves on New Year’s Day 1863. It was a war measure; it applied solely to areas still in rebellion. It freed slaves only in the Confederacy, not in the border slave states. Last year’s essay explained Lincoln’s constitutional justification.

But Lincoln wasn’t done.

The Proclamation transformed the conflict into a crusade not just to preserve the union but to end slavery. It proved a wearyingly long struggle; no end was in sight as the election of 1864 loomed. For many months unsure of his prospects, the president won renomination and a solid re-election victory in the wake of some timely Union victories. That freed him to pursue the ultimate goal: not just to free some slaves, but to abolish the institution altogether through an amendment to the Constitution. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, the text flatly declares, shall exist within the United States.

The Thirteenth Amendment was intentionally limited in scope, explains constitutional historian Herman Belz, “completing and constitutionalizing military emancipation.” Retroactively, it legitimated the Emancipation Proclamation and related measures that had “confiscated” rebel property on grounds of military necessity. But it did so by adopting historic language, that of the old Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which had banned slavery north of the Ohio River. So while it did not grant an array of civil liberties, it made absolute for blacks what was assumed for whites: the personal natural right of liberty originally enshrined in the Declaration of Independence.

In the post-election session of Congress, Lincoln pressed for Congressional approval. The amendment cleared both houses in January 1865. By December enough states had ratified to make it official. The bondage practiced in America virtually from its colonial founding was no more.

The Fourteenth Amendment

Lincoln didn’t live to see this grand finale to his longstanding hostility to slavery. John Wilkes Booth’s point-blank pistol shot ended Lincoln’s life in April. The martyred president’s vice-president, Tennessee Unionist Democrat Andrew Johnson, assumed the presidential mantle. To him fell the task of overseeing the nation’s painful “reconstruction” into “one nation, indivisible.”

Neither temperament nor leadership skills equipped him for the assignment. Acting alone before Congress reconvened, Johnson moved quickly to restore the Southern states and rehabilitate Southern leaders. So accommodating was he to Southern whites that many Northern congressmen were outraged. So in 1866 they passed two landmark bills: a Freedmen’s Bureau Act and a Civil Rights Act. The president vetoed both. Congress overrode both. But what if a future Congress could not muster a two-thirds vote to uphold black rights?

So it was that Congressional leaders rammed through another Amendment to elevate explicit rights of former bondsmen beyond the winds and whims of future politics.

The Amendment’s first section confirms citizenship – in both nation and state – for all born or naturalized in the United States. It then states that state governments cannot (1) abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; (2) deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; (3) deny ... the equal protection of the laws.

The language may sound familiar. Article IV, Section 2 in the original Constitution had granted to all citizens the “privileges and immunities” of each state. And the “due process” phrase is virtually verbatim from the Fifth Amendment.

The echo was deliberate. The congressman who first proposed the Fourteenth Amendment explicitly intended to extend the Bill of Rights to freed slaves. But a deeper question was at stake: the balance of federal-state power, which of course underlay the Southern states claim of a right to secede. Would the amendment, in effect, create a whole new constitutional order, centralizing new coercive powers in the federal government, or merely fix a flaw?

Arguably the Fourteenth Amendment has had a transforming impact, allowing the federal government to extend the reach of its powers. But in 1866 the issue merely continued a debate among prewar opponents of slavery. Some radical abolitionists had condemned the original Constitution as a pro-slavery charter that at the insistence of Southerners protected the institution, but now must be revolutionized. (Chief Justice Roger Taney, in his 1857 Dred Scott ruling, applauded the Constitution on the same grounds to justify denying citizenship to black folk.) But as I explained three years ago, lawyer Lincoln, harking back to the earlier equality language of the Declaration of Independence, argued that the Framers crafted a document temporarily accommodating to the local reality of slavery, but envisioning its eventual extinction under the overriding principles of liberty and equality. Congressional drafters of the 14th amendment shared this latter view, points out Belz. They saw the new text as “an extension . . . or a completion of the Constitution” – a repair rather than a revolution.

And the most basic repair needed was of Taney’s Dred Scott decree that slaves could not be citizens. Were you born in America (or properly naturalized)? Then, countered the Fourteenth Amendment, you’re a citizen of America and your state. That’s the core affirmation.

So proper understanding of the amendment begins with the idea of inclusion. Congress wished to ensure that former slaves enter a privileged circle. Theirs was not just freedom from (bondage), but freedom for (citizenship). Put differently, the Thirteenth Amendment established the negative: the abolition of slavery. The Fourteenth probed into “now what” territory to chart the positive: the status of the former slave. The “all” who were, in the words of Jefferson’s Declaration, “created equal,” emphatically included the race of Africans once forcibly imported into bondage. African-Americans were human beings, therefore endowed with natural rights, therefore free, therefore citizens.

Despite this focused intent, the Fourteenth Amendment has had wide and contested application, down to our own day, to contexts and in contortions that would have astonished its Reconstruction-era framers. For a half-century after Reconstruction, for instance, the Court extended the “due process” clause to prevent government denial of rights – to corporations! For the last half-century, judicial rulings have applied the “equal protection” clause to require government protection of rights – usually for African-Americans and other minorities.

But the most recent example is even more of a stretch. The Amendment actually includes several other sections of rather technical import. Section 4 prescribes that the immense federal debt rung up to fight the war must be paid. On the other hand, the debt of the erstwhile Confederate government, along with any claim for loss of property in slaves, is declared “illegal and void.” At the climax of this summer’s crisis over raising the debt ceiling, some experts cited this section as grounds for President Obama to lift the lid himself so as not to default on any public obligation.

Another section, the third, barred Confederate officials and soldiers, if they had previously held a U.S. or state-level elective office, from election to Congress. And Section 2 laid out an oddly inverse and wordy stipulation implying that citizenship carried voting privileges. If any male citizen of age was denied the right to vote, he could not be counted in the census figures that determined the number of representatives elected from each state.

That was a bit too subtle an incentive to guarantee the franchise to freed slaves. A third Reconstruction Amendment was needed.

The Fifteenth Amendment

By 1868, seven of the 11 former Confederate states had been readmitted. Newly enfranchised African-Americans voted en masse. But what if a white majority one day stripped their ability to vote in spite of Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Congress responded with a simple text that turned out to be not so simple: The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied ... on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

A straightforward sentence – with a hidden invitation. Race alone could not justify denial of voting privileges. But presumably other criteria might be found: a literacy test, perhaps, or a poll tax. Poor whites no less than blacks could thereby be excluded. As white supremacists regained control of Southern governments, they discovered that racist appeals to poor whites were their best tool to entrenching their power. To bar them from the voting booth would be foolish.

Thus was invented “grandfathering.” We use the term today to refer to any privilege retained by some while others no longer qualify. But the original meaning was insidious. You couldn’t vote if you couldn’t pass a literacy test. But if your grandfather could vote, we’ll let you in the polling booth anyway. Blacks out; poor illiterate whites in. Grandfathered!

Next time you hear the term, feel a little uncomfortable, knowing its origin.

By 1900, few African-Americans could exercise their constitutionally guaranteed right to vote. Through the 20th century, however, the franchise gradually expanded again – by further Constitutional amendment, judicial ruling, legislative action and executive enforcement – to women, to 18-year olds, and, yes, finally to African-Americans. Again.

Yet scandalously, as access has widened, actual voting has declined. Perhaps another reason to feel a little uncomfortable as we celebrate the Reconstruction Amendments.

A New Birth of Freedom?

Three amendments, representing liberty, equality, and democracy’s mechanism to secure these two: voting. That water sculpture at Corinth, titled “The Stream of American History,” reminds me of the achievement. Designer Woody Harrell, who also serves as park superintendent, placed barriers small and large to interrupt the flow. Massive blocks represent the bloody battles of the Civil War. Then the waters smooth, with three plates representing the three amendments, and a final admonitory epigram, visible beneath the water: The Civil War was fought over issues of liberty; the cost was high, and many issues remain to be resolved.

Are we worthy, the gurgling whispers to me, 150 years later? Worthy of the tortuous journey of American constitutional government from its drafting in 1787 through its near-fatal crisis four-score years later? Worthy of the melancholy man who led the nation through the crisis and to the abolition of its great contradiction? Worthy of the Constitutional legacy of martyr Lincoln, as embodied in the three Reconstruction Amendments? Worthy enough to deal with those issues yet unresolved?

The Reconstruction of the 1860s created the constitutional foundation for lifting Americans of African descent from the outrage of legal enslavement to incorporation into American society as equal citizens. But it would take a second Reconstruction, the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, to put theory into practice. Intriguingly, each of the amendments themselves contained an innovative mechanism: sections that explicitly empowered Congress to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of the amendments. Once Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Fifteenth Amendment could finally work as intended. The right to vote now brought African-Americans the ultimate expressions of political equality: mayors and state legislators, congressional and Supreme Court seats, and finally a president.

And yet the dream remains incomplete, the martyred Lincoln’s legacy unfulfilled. Is it time for yet another new birth of freedom, a third Reconstruction, to bring social practice into congruence with Constitutional provision, with its clear principle of inclusion? Might we better call it an Era of Reconciliation? And might this decade, the sesquicentennial of the Civil War and the three Reconstruction amendments, be when we “finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds”? We then shall finally say that “these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Professor of History William Woodward joined the Seattle Pacific University faculty in 1974. He specializes in the history of the Pacific Northwest, especially military history, as well as 19th century American culture. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, Dr. Woodward also gives public lectures on history and is a consultant to school districts and historical societies.

Professor of History William Woodward joined the Seattle Pacific University faculty in 1974. He specializes in the history of the Pacific Northwest, especially military history, as well as 19th century American culture. The recipient of numerous grants and honors, Dr. Woodward also gives public lectures on history and is a consultant to school districts and historical societies.

For information about the U.S. Constitution and about Constitution Day, September 17, visit the National Constitution Center.