Return to Response

Return to Response OnScreen Archive

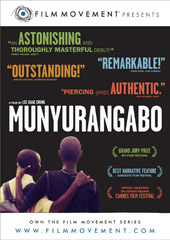

Munyurangabo

Two young friends struggle with their life-and-death cultural differences

Your vocabulary word for today is "Kinyarwanda.” Your vocabulary word for today is "Kinyarwanda.”

Kinyarwanda is the language spoken by virtually the entire population of Rwanda. You’ve probably never seen a movie in the Kinyarawandan language. But you can now, and you should.

Here comes another big word: Munyurangabo.

Munyurangabo is the first feature film made in the Kinyarawandan language. It also happens to be a film praised by movie-lovers at festivals around the world, and it’s coming to DVD in October.

Good news: It’s subtitled. Even better — the people and their country are beautiful, and the story is compelling. Munyurangabo is about a young boy, a machete, a quest for revenge, and the friend who complicates matters.

This suspenseful story builds slowly toward a magnificent conclusion, exploring a question related to another big word: reconciliation. Is reconciliation possible in a country torn apart by war, prejudice, and hatred? Watch it with your friends, and it will get you talking about this.

Munyurangabo was made by an American filmmaker named Lee Isaac Chung. Chung traveled to Rwanda with Youth with a Mission (YWAM), accompanying his wife who is an art therapist helping victims of 1994’s genocidal violence. While he was there, he helped a group of Rwandans learn about filmmaking by making a movie with them. Munyurangabo went on to open at the Cannes Film Festival in 2007, and garnered high honors at other festivals through that year, including the Grand Jury Prize at the AFI Fest.

Chung’s own story is as fascinating as his subject. His family emigrated from Korea and established a farm in rural Arkansas, where he grew up. He went on to study biology at Yale, and then took an entirely different direction, pursuing a growing interest in filmmaking. He studied film at the University of Utah, and became a film instructor himself.

You might wonder what the reviews were like in Rwanda, since it was made by an American. Chung tells me, “Overall, the responses from Rwandese who have seen the film have been more fulfilling to us than the great response we’ve gotten internationally. Of course, like any audience, there are people who find the film boring or too long, or lacking in gunfights. But I’ve been very encouraged by the overall response. I haven’t encountered anyone in Rwanda who has felt that this is not a Rwandese film, so I am very proud of that.”

Chung’s success probably has a good deal to do with his attentiveness to the people there. The plot, which he outlined with his friend Samuel Anderson, was informed and enriched by the people he met when he arrived in Rwanda. His actors were Rwandan, and the stories and jokes they share in the film are their own. Chung says, “I didn’t know the reality of this kind of situation until I got to Rwanda and had long conversations with individuals who underwent similar scenarios. … The process was very organic, and came out of many intimate conversations — a wonderful way to make a film, a [process of] constant discovery and interaction with others."

It’s a pressure-cooker of a movie. You’ll feel the slow burn of its rising suspense as the central characters — a young boy named Munyurangabo (Jeff Rutagengwa) and his friend Sangwa (Eric Ndorunkundiye) struggle over their differing histories and cultures. Sangwa is of the Hutu people, and ‘Ngabo is of the Tutsi, so they should be bitter enemies. Chung’s film questions whether they can overcome the cultural divide, and leaves us to think it over. He does not offer easy answers — rather, he presents us with the horror of the Rwanda’s violent history, and the question of its future, in a poem recited by a man named Edouard near the end of the film.

“The reality of the situation in Rwanda and other parts of the world,” says Chung, “is that progress and reconciliation are rare. Edouard highlights this in his poem. Reconciliation is more than an absence of violence. True justice will occur only when all tragedies — poverty, war, disease — come to cease. Edouard doesn’t say that liberation can come if we do x, y, and z. As you say, he asks a question, ‘How can liberation come?’”

Chung explains that he wanted to highlight this desire for reconciliation through an act of the imagination. “Perhaps faith is a lot like this,” he says, “requiring the act of imagination. Part of me understands the impossibility of this reconciliation on earth, but the other part believes and hopes that it will [happen]. In the meantime, the work is important. I think that’s what the creation of art can embody — the act of memorializing, mourning, preparing — the act of waiting, which I think isn’t very far from the act of questioning.”

(Read Jeffrey Overstreet’s complete interview with Lee Isaac Chung at Filmwell.org.)

By Jeffrey Overstreet (jeffreyo@spu.edu)

Photos Courtesy of Film Movement

|