As CEO of Spark Interaction, Leif Hansen '93 helps people use playful “applied improvisation” exercises to come up with creative solutions to workplace challenges.

As CEO of Spark Interaction, Leif Hansen '93 helps people use playful “applied improvisation” exercises to come up with creative solutions to workplace challenges.

By Jeffrey Overstreet (jeffreyo@spu.edu) | Photos by Luke Rutan

On Saturday, June 30, 2012, artists and writers gathered in the Seattle International Film Festival's auditorium to learn the secrets of Disney’s Pixar Animation Studios. With visions of finding careers in a field that values play, they took notes from the makers of Toy Story and Monsters Inc.

Play is a common theme in Pixar productions. Remember Ratatouille, with the rat who loves to play with food and becomes a full-time chef? Or WALL-E, the robot who turns his trash collection into a treasure hunt?

Wouldn't it be great if going to work always felt like going to a playground?

Pixar animator Matthew Luhn grew up playing in his family’s toy store. “Working at Pixar is like having all of the most creative kids from high school here at one company,” he says. “I don't have to worry about some producer who’s going to get upset at me for goofing around and doing what I do to make the most entertaining movie possible. It’s a rare thing.”

Rare as his experience may be, recent studies in business, neuroscience, and health suggest that we would benefit from more play in our work.

Leif Hansen ’93 wants to make that happen.

Agent of Play

Hansen calls himself the “chief engagement officer” of Spark Interaction, where he helps people “bring work to life through play.” He hosts events that enable people and organizations to “discover and creatively express their core passions in ways that make this world a more magical, loving, and fun place to be.” Asking corporate employees to give ordinary objects arbitrary new names, Hansen gets them fumbling with strange vocabulary until they’re laughing through absurd conversations. Later, they’re singing “Lean on Me” in harmony.

Hansen has been featured on NBC’s Today Show, on PBS online, and in The Los Angeles Times. His work began in the early ’90s, while a communications major at Seattle Pacific University studying the effects of screen-based communication on human relationships. “Already there was something in me that knew we were developing this new culture, and that the rules were changing.”

Sure, he carries a smartphone, but he believes that we can suffer psychological, neurological, and spiritual damage the more we let our relationships depend on a “technocracy.” “We’re becoming more isolated and frustrated,” he says. “Productivity becomes more important than our relationships, the quality of our relationships, the quality of our work.” He laughs, adding, “I call myself a ‘skep-tech.’”

What we're missing, he explains, is the stuff of “applied improvisation.” “We need human interaction, childlike wonder, opportunities for creativity and innovation and experimentation.” So he invites workers to participate in games and theater exercises that take them into unpredictable territory. He calls it “the dark.”

“When we're improvising,” he says, “we're in the dark. We don't know what's coming next.”

In the dark, he says, we make more mistakes. But that’s a good thing. “I will often start workshops by saying that, ‘Our goal is to accelerate the rate of mistakes. Our goal is to fail as much as possible in the next two hours.’ Then you realize, maybe it isn’t that big of a deal. Maybe there’s no such thing as failure.”

He thinks we will be pleased with what can come from the fun of frenzied “failure.” That “fun” is what he calls “the hum.” “Humor, humility, and human — they all have the ‘hum.’ It's the ‘hum.’ that brings us back to earth, to ourselves.” While “the hum” may be hard to hear at first, listen closely — it’s here at SPU.

From Legos to Proteins

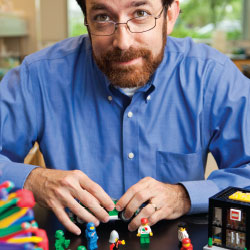

In the office of Associate Professor of Biochemistry Benjamin McFarland, you'll find very little difference between work and play. He even uses toys to help illustrate challenging concepts.

In the office of Associate Professor of Biochemistry Benjamin McFarland, you’ll find very little difference between work and play. He even uses toys to help illustrate challenging concepts.

“I was in the toy store the other day,” says McFarland, “and they had a whole box of tubes that, when you swing them around, make musical notes.” Of course, he bought them to use in his classroom. “With a chemist’s eyes, I saw that you can only play five notes with them. They're quantized in the same way that electrons are quantized. Quantum mechanics comes from the fact that electrons can only be certain values, and these tubes can only play certain notes.”

You’ll also find Legos in his office. “I love Legos,” he says. “There’s something about the level of abstraction with Legos, the way they go together so easily, their bright colors. That’s one of the reasons I became a protein chemist. I love the structures of proteins. They remind me of Legos.”

Similarly, Hee-Sun Cheon, assistant professor of Marriage and Family Therapy at SPU, found her vocation in her own childhood play.

“I was so into theater, into role-playing,” she explains. “I was able to learn how to take different perspectives. That helped me develop empathy. Now, when I hear someone’s stories and struggles, my heart really goes through what they experienced. Without empathy and genuine connection, it is very hard to do therapeutic work.”

Her experience with “drama therapy” has taught her that humor and playfulness can give us a sense of security and freedom, helping us break out of “stuck-ness” at home ... and at work. “In drama therapy, we have a lot of theater games,” she says. “One of them is gibberish. We ask people to use nonsense languages to communicate. The mood is really playful and joyful. They’re bonding.”

That’s the same sort of game that Hansen uses to encourage trust, creativity, and productivity in the workplace. He’s made spontaneous gibberish outbursts part of his Spark Interaction activities. And he says that his seminar participants “report more trust, respect, and empathy with their co-workers, and, in their personal lives, a more creative flow.”

They often tell him, “I haven’t had this much fun since I was a kid!” He claps his hands in triumph. “Exactly!”

“I want students to feel they have permission to play for the purpose of discovery,” says Benjamin McFarland, SPU associate professor of biochemistry, pictured here with some of his Lego minifigures.

“I want students to feel they have permission to play for the purpose of discovery,” says Benjamin McFarland, SPU associate professor of biochemistry, pictured here with some of his Lego minifigures.

Play: What God Wanted All Along

For many of these “play” advocates, play runs as deep as our relationship with God. Luhn points out that when we feel safe, free, and unafraid, we'll find it easier to create. “For Christians,” he says, “that’s like knowing who you are in Christ and feeling the freedom that you get from that relationship.”

For Hansen, “the dark” can be a place for spiritual formation. “When you're in the dark, and you don’t have your ego or your crutches, you’re more capable of trust. You learn to trust other people. You can learn to trust the Spirit.”

Jeff Keuss, professor of Christian ministry, theology, and culture, sees a world of theological significance in the study of play. The Scriptures, he says, show us that God is pleased by play. He even finds affirmations of play in the Sermon on the Mount: “The ‘woes’ are pronounced on those who are so fixed on wealth and accomplishment that they can’t actually live their lives. If you want to think about playfulness as articulating a life worth living, the Sermon on the Mount is a playful engagement.”

He sounds a little like G.K. Chesterton, who wrote, “The true object of all human life is play. Earth is a task garden; heaven is a playground.” Perhaps a childlike spirit would make us more like our creator. Wisdom, as characterized in Proverbs 8, “plays like a child ... creating the world.”

Hee-Sun Cheon agrees. “If we’re made in the image of God, what does that mean? I think God wanted us to be playful.”